Infections In Pregnancy

During pregnancy, there are infections that may cause severe illness to yourself or put your fetus at risk for illness. Thames Valley Midwives has compiled a list of infections in pregnancy clients should be cautious of; we have included recommendations and some of the latest research.

Click the links to see the latest information on Infections in Pregnancy

If you are considering becoming pregnant, or are pregnant, the following precautions should be followed to prevent infections:

- Practice good personal hygiene

Hand washing is one of the best ways to prevent disease transmission. Wash your hands thoroughly and often.

- Wash hands with warm water and soap:

- before eating and before preparing food

- after using the toilet, changing diapers or providing personal care to others or anytime they have become contaminated

- waterless hand sanitizing gels are an excellent addition to hand washing or in times when soap and water is not available.

- Handle food safely:

Meat should be cooked to reach a temperature of:

- whole poultry – 82°C/180°F

- food mixture that includes poultry, egg, meat, fish – 74°C/165°F

- pork, ground meat other than poultry – 71°C/160°F

- Wash all food preparation surfaces that have come in contact with raw meat and then sanitize with a bleach water solution. Use a solution of 1.5 tablespoons of unscented household bleach to 2 gallons of water. Wash fruits and vegetables thoroughly before cooking and/or eating even mushrooms. Wash fruits like raspberries and strawberries thoroughly as they are more difficult to completely remove soil (see toxoplasmosis). Cantaloupes and melons should be thoroughly washed prior to slicing to avoid contaminating the flesh with bacteria from the outside of the fruit.

Determine your immunity to:

- Rubella (German measles). You can have a simple blood test to determine if you are immune. If you are not immune, you can have a vaccine to prevent you from getting the virus

- Chickenpox. You can have a simple blood test to determine if you are immune. If you are not immune, a vaccination may be recommended to prevent the disease

For more information contact the Middlesex London Health Unit Communicable Disease Division at 663-5317, ext. 2330, Health Connection at 850-2280

What is Coronavirus (COVID-19)?

Coronavirus disease 2019 is a respiratory illness that can spread from person to person. The virus was first identified in Wuhan, China but spread worldwide rapidly. On March 12th, 2020, the World Health Organization declared a global pandemic.

COVID-19 variants (mutations) were then seen over the next few years including Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta and Omicron. Some variations enabled COVID-19 to spread more easily, caused more severe illness, required different treatments and reduced vaccine effectiveness.

On May 5th 2023, the Public Health Agency of Canada declared that COVID-19 no longer constituted a public health emergency.

Can I still get COVID-19?

COVID-19 spreads very easily through close contact with people within about 6 feet from droplets when an infected person coughs or sneezes. It is also possible to get COVID-19 from touching infected surfaces or objects, and then touching your mouth, eyes or nose.

What are the symptoms of COVID-19

Coronavirus causes mild to severe respiratory illness which can vary from person to person also varying with different age groups and depends on the variant. Some of the more commonly reported symptoms include:

- New or worsening cough

- Fever – temperature equal to or over 38°C

- Shortness of breath or difficulty breathing

- Feeling feverish

- Chills

- Fatigue or weakness

- Muscle or body aches

- New loss or smell or taste

- Sore throat

- Runny nose

- Headache

- Gastrointestinal symptoms (abdominal pain, diarrhea, vomiting)

- Feeling very unwell

Children have been more commonly reported to have abdominal symptoms, and skin changes or rashes.

The severe complications for some patients include pneumonia in both lungs, multi-organ failure and in some cases death. These severe symptoms are widely described in older people, the immunosuppressed and those with long-term conditions such as diabetes, cancer and chronic lung disease. These symptoms could occur in pregnant people so should be identified and treated promptly.

Symptoms may take up to 14 days to appear after exposure to COVID-19 and can be transmitted to others even if they show no symptoms.

How can I protect myself and my family?

- COVID-19 vaccination is recommended during pregnancy in any trimester and while breastfeeding. Presently, preference is given for the use of mRNA vaccinations during pregnancy as more data on safety and efficacy during pregnancy is available for these vaccines. (SOGC 2023)

- While masking is no longer mandatory in public places, you may still consider wearing a mask where social distancing cannot be practiced consistently or inside buildings such as stores, public transportation, shopping areas.

- Avoid close contact with people who are sick or stay home if you have symptoms of COVID-19.

- Avoid touching your eyes, mouth and nose with unwashed hands

- Wash your hands often for at least 20 seconds with soap and water. Use an alcohol-based hand sanitizer that contains at least 60% alcohol if soap and water are unavailable.

- Sneeze or cough into a tissue or the bend of your arm

- Clean and disinfect frequently touched surfaces and objects such as toys, toilets, phones, tablets, electronics, door handles, bedside tables, television remotes.

COVID-19 and Pregnancy – the Risks:

Both Canadian and international reports have highlighted increased risk of severe illness, including hospitalization and admission to an Intensive Care Unit (ICU), among pregnant persons diagnosed with COVID-19, compared to their non-pregnant counterparts. Canadian data estimates that among pregnant persons infected with SARS-CoV-2 the rate of hospitalization was 7.8% and the rate of ICU admission was 2.0% (SOGC 2023).

Expert opinion at this time is that the fetus is unlikely to be exposed during pregnancy or congenital effects of the virus on fetal development. Increased risk of preterm birth has also been documented among pregnant women/persons diagnosed with COVID-19 (SOGC 2023).

COVID-19 and the Newborn:

The CDC position statement is that:

- Infections causing COVID-19 in newborns born to mothers with COVID-19 are uncommon.

- Some newborns have tested positive for the virus that causes COVID-19 shortly after birth. It is unknown if these newborns got the virus before, during, or after birth from close contact with an infected person.

- Most newborns who tested positive for the virus that causes COVID-19 had mild or no symptoms and recovered. However, there are a few reports of newborns with severe COVID-19 illness.

- Preterm (less than 37 completed weeks gestation) birth and other problems with pregnancy and birth have been reported among clients who tested positive for COVID-19 during pregnancy. It is unknown whether these problems were related to the virus that causes COVID-19.

Evidence suggests that the risk of a newborn getting COVID-19 from the parents are low, especially when appropriate precautions before and during care of the newborn if you test positive for COVID-19.

- Wash your hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds before holding or caring for your newborn. If soap and water are not available, use a hand sanitizer with at least 60% alcohol.

- Wear a mask when within 6 feet of your newborn.

- Keep your newborn more than 6 feet away from you as much as possible.

- Never put a mask or face covering/shield on your baby or any child under the age of 2. This could increase the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) or accidental suffocation and strangulation. Babies move frequently. Their movement may cause the plastic face shield to block their nose and mouth, or cause the strap to strangle them.

- You should continue to breastfeed your baby if this is your method of feeding or express your milk.

If your isolation period has ended, you should still wash your hands before caring for your newborn, but you don’t need to take the other precautions.

What happens if I am in self-isolation for COVID-19 and require urgent attention for my pregnancy or labour?

If you are pregnant and have suspected or tested positive for COVID-19, you should advise your midwife by phone during office hours by calling the main desk to reschedule your appointment.

If you are in labour or require a hospital assessment urgently for your pregnancy, and are self-isolating, your midwife will make arrangements to meet you in a specialist isolation room for assessment. You must wear a mask for the duration of your appointment or hospital stay.

Currently the recommendation from the Royal College of Gynaecologists UK suggests continuous fetal monitoring is implemented to ensure your baby’s wellbeing due to the increased risk of fetal compromise.

Information adapted from: Society of Obstetrics and Gyneacology Canada (SOGC), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website, Middlesex Public Health Unit, World Health Organization, and Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists in U.K. Last modified March 2020.

Additional Resources –

SOGC COVID-19 Resources Handout

SOGC Statement on pregnant workers during the COVID-19 pandemic

SOGC Statement on COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy

SOGC Statement on pregnant people in the ICU’s with COVID-19

What is Group B Strep (GBS)?

Group B Strepococcus (GBS) is a common gram-positive bacteria found in the vagina, rectum or urinary bladder. Most people have no symptoms and we generally do not know it is there. It is unknown why some people carry it, and some people do not. 15 to 40% of people who are pregnant will have GBS in their vagina and/or rectum at any time, and it comes and goes, with rates varying by study populations, specimen collection and culturing techniques. If we test different people to see if the bacteria is there over a certain time period, we might find it is sometimes there, never there, or always there.

In Ontario in 2019, approximately 19% of pregnant people who were screened for GBS between 35 and 37 weeks’ gestation had a positive result. (4) Of pregnant people who did not undergo screening for GBS at 35 to 37 weeks’ gestation, 0.5% had already screened positive for GBS bacteriuria through a urine test.

Between 40 to 70% of colonized (GBS positive) pregnant people pass the bacteria on to their babies if untreated. The most common way to pass on GBS is at the time of birth. Most babies are not affected by GBS. Early onset group B strep occurs within the first seven days of life, and incidence rates vary. Before the widespread adoption of prevention strategies such as intravenous antibiotics given during labour in the 1980s, the incidence was estimated at 3/1000 live births. This has dramatically changed over several decades; in Ontario in 2019, there were only 35 cases of early onset GBS in neonates, a rate of 0.23 per 1000 live births (around 1 to 2% if untreated).

Babies who are infected can develop mild to severe conditions (case fatality rates currently 5% to 9%) such as blood infection (bacteremia), lung infection (pneumonia), respiratory infection, meningitis (inflammation in the brain and spinal cord), and stillbirth or death. One study (Davis, et al. 2001)

CDC surveillance data from 1999 to 2005 found that 83% of early onset GBS cases had bacteremia, 9% had pneumonia, and 7% had meningitis. (5) In a 2008 Toronto study, similar proportions were noted: 64% bacteremia, 23% pneumonia and 12.5% meningitis. (6)

Ontario case fatality rates range from 2% to 17% over the past five years, with an average case fatality rate of 5%. (7)

Testing:

During the course of your pregnancy, your midwife will send a urine specimen to the lab to check for any GBS infections. If you have a GBS UTI (urinary tract infection), your midwife will discuss and offer treatment during pregnancy and intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis when you go into labour or when your waters break. Your midwife will be able to send a prescription to the pharmacy of your choice.

Around 35-37 weeks’ gestation, your midwife will discuss and offer testing for GBS using a swab that you will do by yourself in the washroom (research suggest that self-sampling may capture more positive GBS results). It takes around a week to receive results. We do not need to test before this time as research has shown that it is not beneficial to give antibiotics during pregnancy and in over 65% of cases, GBS grows back again before labour begins. Your midwife will let you know at your next appointment whether you are colonized with GBS or not.

The GBS test correctly identifies when someone has GBS 77% of the time. In other words, approximately 23% of birthing parents with a negative antepartum culture screen will go on to be GBS positive in labour, while 10% of birthing parents with a positive antepartum culture will go on to be GBS negative in labour. The concern with these findings is that some pregnant people who have GBS at birth will be missed and therefore will not receive IAP, while a smaller proportion may receive unnecessary IAP.

This means there are 52% to 82% of term neonates who develop early onset GBS are born to individuals who screened negative for GBS prenatally, although the absolute risk of negative prenatal screen is low. It is unclear whether these cases are associated with a false-negative screening result or colonization after screening has occurred.

Two research studies suggest that Black pregnant people may have higher rates of conversion from a negative antepartum GBS culture to a positive intrapartum culture, as well as higher rates of infants with early onset GBS despite screening negative on antepartum culture. These findings suggest a racial disparity and further research is needed to understand why, although researchers have hypothesized that it could be due to differential rates of GBS acquisition and clearance, inequitable delivery of IAP, or other systematic health disparities faced by Black pregnant people.

Testing for GBS is a choice that we offer to everyone at Thames Valley Midwives. If you choose to do the test and test positive for GBS, research has shown around 31% of people will receive antibiotics in labour. This choice reduces early onset disease in babies by 65% to 86% when compared to babies of pregnant people who do not receive antibiotics.

Is there a rapid GBS test that I can do during labour?

Although ideal, unfortunately the development of a reliable rapid test continues to be ongoing. Rapid tests have yet to be used outside of a research study setting.

Are there ways to prevent GBS in pregnancy?

Several strategies to prevent GBS transmission and disease have been proposed. These aim to reduce or eliminate GBS colonization in the birthing parent before birth, thereby reducing the risk of transmission to the neonate. Evidence on the use of probiotics and homeopathic or natural remedies to prevent GBS colonization at birth in the birthing parent is summarized below.

- Probiotics – Microbial balance in the vagina can help protect clients from GBS colonization. Supplementation with probiotics, specifically lactobacillus, may improve the microbial balance, inhibiting growth and adhesion of streptococci and therefore reducing GBS colonization. Seven studies have been identified that investigated the effect of oral probiotics for prevention of GBS colonization in the birthing parent at or before birth. Four RCTs compared the use of oral probiotics starting in the antepartum period with a placebo, while one RCT compared the use of oral probiotics with no treatment or the usual care. Treatment regimens varied across studies.

- Meta-analyses show that oral probiotics:

- Likely reduce GBS colonization close to delivery (from 35 weeks) in the birthing parent

- Likely have no side effects

- Meta-analyses show that oral probiotics:

- No studies could be identified that investigated the effect of dietary sources of probiotics for the prevention of GBS colonization in the birthing parent before or at birth.

- No studies have examined the impact of probiotic use on transmission of GBS or the development of early onset GBS in neonates. The available research also does not demonstrate an optimal duration or dosage for probiotics, and it does not provide information on the efficacy of alternate sources of probiotics, such as food.

- Despite gaps in the research, some clients may prefer probiotics as a means of reducing the potential need for IAP at birth. It is also important to consider the question of access, as probiotics can be costly. In Canada, they are considered a natural health product, and therefore they do not carry a drug identification number (DIN) and are not covered by insurance, including the Ontario Drug Benefit (ODB) for those enrolled in Ontario Works (OW), or the Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP). Access to probiotics may also be limited in areas where natural health products are not readily available.

2. Homeopathic and Natural Remedies – No studies could be identified on the use of homeopathic or natural remedies (including but not limited to garlic suppositories, vitamins and echinacea) in the antepartum period for prevention of GBS colonization at birth.

Treating GBS:

When you go into established labour or your waters break, your midwife will offer treatment using intravenous antibiotics. Penicillin G is the most common antibiotic used to treat GBS. It is given every 4 hours through an intravenous drip until your baby is born and two doses are required to ensure the treatment is adequate. If you have an allergy to Penicillin, your midwife will discuss an alternative antibiotic to treat GBS.

If the intravenous drip is only required for GBS, the tubing can be removed between treatments, but the small tube in your hand or arm will stay in place using special tape to ensure it does not become loose. This will enable you to move around freely still. GBS treatment can be done at home if you are planning a home birth, and you are in established labour. If your waters have broken, you have no contractions and you are planning a home birth, your midwife will discuss your course of care, and you may be required to come to hospital to have your baby.

Are there risk factors that are associated with GBS colonization in the birthing parent?

Associated risk factors in the birthing parent have been studied; however, the research investigating these factors varies in quality.

- Colonization in a previous pregnancy – Systematic review evidence suggests that in term pregnancies, birthing parents who were colonized with GBS in a previous pregnancy are more likely to be colonized in a subsequent pregnancy especially if they were heavily colonized.

- Research suggests individuals with a BMI > 25 kg/m² have increased odds of GBS colonization

- Researchers have examined the association between diabetes (type 1, type 2, gestational diabetes and pregestational diabetes) and colonization status. Evidence consistently shows that both gestational diabetes and pregestational diabetes are associated with GBS colonization. Gestational diabetes may be associated with changes in vaginal lactobacillus, which may facilitate GBS colonization.

Are there specific risk factors that increase your baby’s chance of getting early onset GBS infection?

Yes, there are specific risk factors that will increase your baby’s chances of getting early onset GBS infection despite widespread use of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis. Understanding the significant risk factors that arise during the antenatal and intrapartum periods can allow for timely and appropriate follow-up of the neonate in the early postpartum period. Despite these associations, research also shows that intrapartum risk factors may be absent in 30% to 50% of early onset GBS cases. These risk factors include:

- Screening positive during a urine sample in your pregnancy.

- You reach full term and your waters break, and it seems as though your labour will last longer than 18 hours.

- A fever during your labour over 38°C.

- An infection called chorioamnionitis of the amniotic fluid around your baby in labour may increase the risk.

- Preterm labour (less than 37 weeks gestation) or your baby weighs less than 2500 grams (low birth weight).

- You had a previous baby with GBS disease

- You have (or had) a bladder or kidney infection, which was caused by GBS bacteria.

- Your waters have been broken for over 18 hours. In a 2011 case-control study in which intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis use was widespread and overall risk of early-onset sepsis (EOS) was consequently low.

- Practices such as frequent vaginal examinations and membrane sweeping in labour have been observed during some studies. Because such practices may be used more frequently in the presence of other risk factors, this relationship may be confounded.

- You have a multiple pregnancy – this may increase the risk.

Can I take the test and decide in labour if I would like intrapartum antibiotic prophylactic treatment based on risk factors if I test positive?

Yes, this is another option you may choose. With this choice, about 3.4% of women receive antibiotics during labour, if more than one risk factor presents. This choice reduces early onset GBS in babies by 51% to 75% compared to babies of people who do not receive antibiotics at all.

What if I choose not to take the test?

If you decide to not screen for GBS prior to labour, you will be considered GBS “unknown.” Some clients choose this option as they wish to minimize exposure to antibiotics and are comfortable with the possibility of a small increased risk of EOGBSD, the culture-screening and risk-factor approach may be an appealing option, as it appears to limit overall risk and result in less frequent antibiotic use. During your labour, your midwife will inform you if risk factors present and offer you an informed choice discussion about commencing intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis at this point and/or other ongoing plans.

I am planning a home birth but have tested GBS positive. Can I still have a home birth?

Intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis is routinely offered and administered by midwives to individuals who are planning home births or who prefer to labour at home for as long as possible. Your midwife will provide a prescription to pick up in preparation for your home birth. We will provide you with all the necessary equipment we will need to start your IV at home, and bring epinephrine to your home in the unlikely event of an emergency such as anaphylaxis.

What if my labour is fast and I do not have time to get the antibiotics if I test positive?

Research has not identified any effective strategies for preventing GBS infection to the baby during the postpartum period beyond watching your baby closely for signs of infection. However, most babies will not become infected with GBS.

Are there any risks of getting antibiotics?

Antibiotics can cause mild to serious health problems for you and your baby. Approximately 10% of people report penicillin allergies, with less than 1% reporting a severe reaction, such as anaphylaxis. Allergy testing could be considered to rule out an ongoing allergy to penicillin.

Relatively common side effects of antibiotics for you include: yeast infections for you until around 1 month postpartum and your baby (not statistically as significant), and minor allergic reactions to the antibiotic, such as a rash, nausea, vomiting or diarrhea. Less common side effects can be more serious: like an allergic reaction causing breathing difficulties, hives, wheezing and shortness of breath, resistance to antibiotics, other bacteria related health concerns to your baby, and an increased risk of your baby developing asthma and allergies.

The first microbes infants are exposed to are crucial for the establishment of microbial communities and the development of the immune system. A recent systematic review investigated the effects of IAP on the infant microbiome compared with those who did not have a GBS-positive parent and who had not been exposed to IAP:

- Lower bacterial diversity

- Lower relative abundance of Actinobacteria, especially Bifidobacteriacea

- Larger relative abundance of Proteobacteria Long-term effects of these changes are unclear.

What are the management plans I can choose if my waters break?

You can look at our labour page for information on GBS and how it affects you if waters break but there are no contractions or your contractions are not yet regular. We have broken down the different options and strategies to manage GBS so that you can make a fully informed decision. Your midwife will discuss these options around 35-37 weeks gestation. If you are unsure about any of the management plans, you should discuss your options with your midwife at your next appointment.

I’ve had my baby, now what?

For more information on GBS in the postpartum, click here.

References:

- AOM clinical practice guideline on GBS No. 19: Antepartum, Intrapartum and Postpartum Management of Group B Streptococcus

- AOM clinical guideline summary on postpartum management of the neonate and GBS

- SOGC GBS infection in pregnancy handout

- Better Outcomes Registry and Network (BORN) Ontario. Group B Streptococcus Screening Results.

- Phares CR, Lynfield R, Farley MM, Mohle-Boetani J, Harrison LH, Petit S, et al. Epidemiology of invasive group B streptococcal disease in the United States, 1999-2005. JAMA [Internet]. 2008 May 7;299(17):2056–65.

- Hamada S, Vearncombe M, McGeer A, Shah PS. Neonatal group B streptococcal disease: incidence, presentation, and mortality. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstetricians [Internet]. 2008 Jan;21(1):53–7.

- Public Health Ontario. Group B Streptococcal Disease, Neonatal (Group B strep) [Internet]. 2021.

What is Chickenpox?

Chickenpox is an infection caused by the varicella-zoster virus. It is most common in children. Infection with Chickenpox may begin with a mild fever, followed in a day or two by a rash, which may be very itchy. The rash starts with red spots that soon turn into fluid-filled blisters. In a few days, crusts form over the blisters. The chickenpox rash usually appears 14-21 days after exposure to the virus.

Chickenpox is an infection caused by the varicella-zoster virus. It is most common in children. Infection with Chickenpox may begin with a mild fever, followed in a day or two by a rash, which may be very itchy. The rash starts with red spots that soon turn into fluid-filled blisters. In a few days, crusts form over the blisters. The chickenpox rash usually appears 14-21 days after exposure to the virus.

How is Chickenpox spread?

The Chickenpox virus spreads very easily through the air or through direct contact with the fluid from a chickenpox blister. It is highly contagious among people who are not immune and can spread within childcare facilities, schools and families.

Chickenpox can be passed onto an unborn baby and a newborn if a client develops chicken pox during pregnancy or after birth.

When is it contagious?

Chickenpox is contagious usually 1-2 days and possibly up to 5 days, before the onset of the rash. It remains contagious until 5 days after the onset of the rash or until all the lesions have crusted over, whichever comes first.

Chickenpox and Pregnancy: The Risk

Pregnant clients who have never had Chickenpox can develop severe illness if they acquire Chickenpox while pregnant. Chickenpox can affect the developing baby if the client becomes infected in the first half of pregnancy and the newborn baby can develop severe or even life-threatening chickenpox if the client has the infection around the time of delivery.

How do I know if I’m immune to Chickenpox?

If you have a past history of Chickenpox, you will have antibodies to protect you from getting Chickenpox again. If you cannot recall previous infection, you can have a blood test to determine if you have any antibodies to Chickenpox. Even if you don’t remember having Chickenpox, the majority of people tested show antibody protection.

What if I have no immunity, and am exposed to a case of Chickenpox?

If you are pregnant and have no immunity, we advise you to see your family doctor or attend the walk-in clinic as soon as possible after the exposure.

You may be advised to receive an injection of varicella-zoster immune globulin (VZIG) to help prevent severe infection.

What is Varicella-Zoster immune globulin (VZIG)?

VZIG is a blood product that provides immediate protection against Chickenpox. It is used in people who have never had Chickenpox and have been exposed to someone with Chickenpox and are either pregnant or have problems with their immune system.

What about the Chickenpox vaccine?

Chickenpox vaccines (Varivax III™ or Varilrix™) should NOT be used during pregnancy.

Those who are 12 months to 12 years old receive two doses 3 months apart. Those who are 13 years or older, receive two doses at least 6 weeks apart. Clients who do not have protection from Chickenpox, as determined by the blood test, and are considering a future pregnancy should receive the vaccine. Clients should not become pregnant for one month after receiving the second needle. A reliable form of birth control must be used during that time.

Chickenpox vaccine is free to children born on or after January 1, 2000 and for high-risk people of all ages who have not had the chickenpox. There is a charge for the vaccine if you do not fit into one of these categories. Discuss the fee with your doctor or a public health nurse at the health unit.

What about shingles (herpes-zoster)?

Shingles is a reactivation of the Chickenpox virus that has stayed in the body since the original infection. It results in fluid-filled blisters along the nerve pathway where the virus resides. A person with open sores is contagious for a week after the appearance of these lesions. Shingles is not as contagious as Chickenpox but an unprotected person in direct contact with the fluid-filled blisters can get Chickenpox. Shingles is not spread through the air.

For additional information on Chickenpox refer to the Middlesex-London Health Unit factsheet Chickenpox. For further information, contact the Communicable Disease and Sexual Health Service at 519-663-5317 Ext. 2330.

Information adapted from: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website “Canadian immunization guide“, Middlesex Public Health Unit “Chickenpox and Pregnancy“, and Canadian Paediatric Society. Last modified January 2016.

What is Rubella?

What is Rubella?

Rubella is commonly known as “German measles”, an infection that affects the skin and lymph nodes, caused by a virus. It is spread from an infected person by coughing, sneezing and saliva. Rubella starts with mild flu-like symptoms followed by a rash, although half the people with rubella have no symptoms at all. It is most contagious a few days before and after the rash appears, and lasts around 3 days.

Who is most at risk?

While rubella usually causes only mild illness in children, it can cause serious consequences for the fetus if a pregnant client becomes infected. If the client becomes infected within the first 10 weeks of pregnancy, the chance of giving birth to a baby with Congenital Rubella Syndrome (CRS) may be as high as 90%. Infants with CRS may be born deaf or blind. They may have damage to their hearts or mental disabilities. Miscarriages are also common.

The risk of fetal abnormalities decreases if exposure to rubella occurs after the first trimester. At 12-20 weeks of pregnancy, there is a 10-20% risk of CRS. Infection during this part of pregnancy mainly results in deafness. After 20 weeks, the risk of abnormalities in the baby is almost zero. However, if a client contracts rubella near the end of pregnancy, the baby is likely to be born with rubella infection and can pass the infection to others.

How often are babies born with Congenital Rubella Syndrome (CRS)?

CRS is rare in Ontario as most clients have been vaccinated against it. Three cases of CRS were reported to the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care from 1995-2005, and only two cases in 2006.

How safe are schools during a rubella outbreak?

Schools in Ontario are generally well protected from rubella as 95% of school students have been vaccinated against rubella. The rubella vaccine has been available since 1969. One dose of MMR vaccine is 95% effective at preventing rubella. Most children less than 15 years of age have received two doses of the MMR vaccine. (The two doses are offered to provide good protection against red measles. Only one dose of vaccine is needed for rubella protection.)

Public health units are informed as soon as rubella is diagnosed. If the person with rubella is a student, then all unvaccinated students who attend the same school are immediately excluded under the authority of the Immunization of School Pupils Act. Once unvaccinated students are excluded from school, it would be rare to see further transmission of rubella in the school as all remaining students would be immunized.

What about the general community?

It is uncommon to see sporadic cases of rubella in the community. Most people in Ontario have been vaccinated or had the illness at a young age, and are therefore immune. Outbreaks are usually confined to unvaccinated communities.

If I’m already pregnant, can I get vaccinated?

No. Vaccination cannot be given to pregnant people.

What should I do if I’m pregnant and live or work in a setting where there has been rubella?

Your midwife will offer a blood test at the beginning of your pregnancy as part of your early pregnancy blood work to determine whether you are immune or non-immune to rubella. If you have seen your family doctor prior to seeing a midwife, you can request your results from their office.

Immune clients:

Documented immunity during the current pregnancy provides very good protection against rubella. For immune clients, there is a very small risk of being reinfected after exposure; however the chance of CRS developing after reinfection is extremely small.

Non-immune clients:

If the blood test shows that you are not immune to rubella, you should do the following:

In communities where rubella is known to be circulating, avoid group activities such as school, work or church:

- Avoid contact with anyone with a rash

- Avoid contact with anyone who may have been exposed to rubella

- Avoid sharing drinks, lipstick or cigarettes and any other activities that allow for transmission of rubella through saliva

- Try to keep at least 1 metre away from others in public places

- Wash your hands thoroughly and frequently with soap and water or use a hand sanitizer containing 60 – 70% alcohol

- Make sure that your partner, children and others around you are protected from rubella. Unprotected children and partners should be vaccinated

If you have been exposed to rubella and are non-immune, take the following precautions to avoid spreading infection to others:

- Avoid using public transportation such as airplanes, buses and trains

- Cover your mouth while coughing and sneezing; dispose of tissues

- Avoid unnecessary travel outside your community

- Your midwife will do blood tests to check whether you have become infected

- Clients who develop rubella during pregnancy will be referred by their midwife to an obstetrician for further assessment and counseling

What can I do to prevent rubella before pregnancy or after having a baby?

If you are of child bearing age but not pregnant, visit your doctor to have a blood test to ensure you are immune to rubella. If you are not immune, get your MMR vaccine and wait at least one month before trying to become pregnant.

References:

- Middlesex health unit – Rubella and pregnancy

- Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS) – Rubella in pregnancy

- Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS) – measles, mumps and rubella vaccine

- CDC Government of Canada – Rubella

What is Toxoplasmosis?

Toxoplasmosis is a disease caused by a parasite found in undercooked meat and in the feces of cats. Toxoplasmosis can be passed from the pregnant person to the developing baby and may result in miscarriage or birth defects.

How is it spread?

- Eating raw or undercooked meat that contains the parasite

- Handling kitty litter, garden soil or sand which may contain cat feces

What are the symptoms?

- There are usually no symptoms

- When they do occur, they include fever, sore throat, tiredness, muscle pain and swollen glands in the neck

How do I prevent Toxoplasmosis during pregnancy?

- Wash your hands before eating and after handling raw meat or having contact with soil possibly contaminated with cat feces

- Meat should be cooked to reach a temperature of:

- Whole poultry – 82°C/180°F

- Food mixture that includes poultry, egg, meat, fish – 74°C/165°F

- Pork, ground meat other than poultry – 71°C/160°F

- Wash all food preparation surfaces that have come in contact with raw meat and then sanitize with a bleach water solution. Use a solution of 1.5 tablespoons of unscented household bleach to 2 gallons of water

- Wear gloves when working in the garden. Avoid touching your mouth while working. Thoroughly wash hands after removing the gloves

- Avoid cleaning kitty litter boxes

- Cover sand boxes when not in use

For more information contact the Communicable Disease Division at 663-5317 ext. 2330.

Information Adapted from: Control of Communicable Diseases Manual Last updated August 2017.

References:

- CDC – Parasites Toxoplasmosis

What is Listeriosis?

Listeriosis is the name of a rare infection caused by eating food contaminated with a bacterium called Listeria monocytogenes – a type of food poisoning. These bacteria are found everywhere in the environment. It is commonly found in soil, decaying vegetation and water. People and animals can be carriers of listeria bacteria and never get sick.

Outbreaks of listeriosis have been caused by consuming unpasteurized (raw) milk, soft cheese, raw fish (e.g. sushi), vegetables and ready-to-eat meats (like lunch meat). Listeriosis can cause mild-flu like symptoms such as fever, chills, muscle aches and diarrhea or upset stomach. Symptoms can develop 3-70 days after eating contaminated food.

Despite listeriosis being rare, if contracted during pregnancy, listeriosis can be passed onto the baby, leading to miscarriage, premature delivery, stillbirth or infection of the newborn.

According to the CDC, hispanic clients are 24 times more likely to acquire a listeria infection.

Recommendations during pregnancy:

Motherisk was a Toronto based program based out of Mt Sinai Hospital but Government funding was cut and unfortunately the program was discontinued in 2019. Prior to this, their most up to date recommendations for pregnant clients and listeriosis in 2010 included; no longer advising clients to avoid deli meat, raw fish like sushi or soft cheeses (like Brie, Camembert, blue veined and Mexican cheeses) during their pregnancy as the risk of being infected by L monocytogenes is extremely low when food is handled and stored appropriately. They make recommendations that:

- You acquire these food sources from a reputable store or restaurant

- Choose pasteurized options (most Canadian food sources are pasteurized unless you purchase raw foods from local farms)

- Store the food appropriately,

- Consume them in moderation

- Consume soon after purchase

The CDC has conflicting information regarding the consumption of the above food groups and advises pregnant clients to avoid them all together.

Hard cheeses, cream cheese, cottage cheese and shelf-stable items are not associated with listeriosis and are generally safe to consume.

Raw or unpasteurized milk, unpasteurized fruit or vegetable juices such as apple cider can contain listeriosis and should be avoided if possible whilst choosing pasteurized options during your pregnancy.

Eggs & Salmonella:

Clients should avoid raw or soft-cooked eggs (with the exception of pasteurized eggs) throughout their pregnancy due to the risk of Salmonella food poisoning, which is a more common food-bourne illness causing uterine infection.

Salmonella typically presents with fever and gastrointestinal symptoms like nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and stomach cramps. The bacteria in approximately 4% of cases can lead to uterine sepsis – an infection in the uterus where the baby is growing.

Homemade foods that often contain raw or unpasteurized eggs include mayonnaise, salad dressings, custards, ice cream, raw cookie dough, egg nog and cake batter. Commercial products are made with pasteurized eggs and are therefore safer to consume.

References:

What is Fifth Disease?

Fifth Disease is a mild rash caused by a virus called Parvovirus B19. Fifth Disease is also known as slapped face disease.

About half of pregnant people are immune to Fifth Disease as they contracted it as a child themselves; this usually protects their baby from getting the disease. Pregnant people who are not immune usually have only mild illness if they are exposed and generally their babies do not have any problems.

There is a small risk of the unborn baby developing severe anemia due to an infection during pregnancy, which can result in miscarriage in less than 5%. The risk is lower for exposures in the second half of pregnancy than in the first half.

Tests can be done to see if you are immune to the virus that causes Fifth Disease. If you are pregnant and think you may have been exposed to Fifth Disease, consult your midwife.

How is Fifth Disease Spread?

The Fifth Disease virus is spread through secretions of the nose and mouth by sneezing and coughing or by touching contaminated article such as a used facial tissue and then touching your own mouth or nose.

When is it contagious?

A person with Fifth Disease can spread the infection to others before the rash develops. By the time the rash appears it is no longer contagious. Children with Fifth Disease can return to school and will not spread the infection to others after the rash appears. About half of all adults have had Fifth Disease and will not develop the infection again.

What are the Symptoms?

Fifth Disease begins with a mild illness that may result in a fever, tiredness, muscle aches and a headache. A few days later a very red rash appears on the child’s face- thus the name “slapped face disease.” A lacey rash also appears on the child’s body. This rash can last for days to weeks and can come and go. Adults may develop joint pain, which lasts a few weeks.

Prevention:

– Practice good hand washing

– Cover nose and mouth while coughing and sneezing and carefully dispose of used facial tissues

– Do not share eating utensils

For further information, contact the Middlesex London Health Unit Communicable Disease Division at 663-5317, ext. 2330.

References:

- Chin, J (ed.). (2000) Control of Communicable Diseases Manual (17th ed.) Washington, DC: American Public Health Association.

- CDC (2017) – Parvovirus B19 and Fifth Disease in pregnancy

What is influenza?

The Flu otherwise known as Influenza is a respiratory infection caused by a virus. It can cause sickness for a few days up to a few weeks. Symptoms vary but may include; runny nose, cough, fever, sore throat, headache, muscle aches and tiredness.

Pregnant people are more susceptible to influenza due to changes in their immune system, heart and lung function, or current health conditions like diabetes, asthma, etc. Complications of influenza can lead to pneumonia, hospitalization and even death.

How does it spread?

Influenza spreads easily from an infected person through coughing and sneezing. It can also be picked up by touching unwashed hands, surfaces and objects such as toys.

How can I protect myself during pregnancy?

Although it is not always possible to prevent becoming sick, but you can do a few things to reduce your chances of the illness whilst pregnant.

- Wash your hands thoroughly with soap and water or alcohol based sanitizers. Clean your hands after handling tissues, blowing your nose, shaking hands, touching objects around you and before preparing and eating food

- Get the flu shot. People who receive the vaccine can still get influenza, but if they do, it is usually milder. However, the vaccine will not protect against colds and other respiratory illnesses that may be mistaken for influenza

- Stay home if you feel sick. The midwives request that you do not attend clinic appointments if you are sick with flu or flu-like symptoms due to the risk of passing it on to other pregnant clients, newborn babies or midwives

Is the flu shot safe in pregnancy?

Flu shots have been given to millions of pregnant people over many years with a good safety record. There is a lot of evidence that flu vaccines can be given safely during pregnancy; though these data are limited for the first trimester. CDC and ACIP recommend that pregnant clients get vaccinated during any trimester of their pregnancy. See Seasonal Flu Vaccine Safety and Pregnant Women for more information.

Pregnant clients should get a flu shot, and not the live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV), also known as nasal spray flu vaccine. Flu vaccines given during pregnancy protect both yourself and your baby from flu. Vaccination reduces the risk of flu-associated acute respiratory infection in pregnant people by up to one-half. Pregnant people who get a flu vaccine are helping to protect their babies from flu illness for the first several months after their birth, when they are too young to get vaccinated. CDC has a number of recent studies on the benefits of flu vaccination for pregnant people.

What should I do if I get influenza?

For mild symptoms of the flu or cold, we recommend rest, fluids and Acetaminophen (“Tylenol”) to reduce any fever or aches.

If your symptoms worsen within the first 48 hours, we recommend seeing your family doctor or attend a walk-in clinic for antiviral treatment. Oral Oseltamivir is the preferred for treatment of pregnant clients because it has the most studies available to suggest that it is safe and beneficial.

When should I call my midwife?

If you are pregnant and have any of these signs, call your midwife:

- Difficulty breathing or shortness of breath

- Pain or pressure in the chest or abdomen

- Sudden dizziness

- Confusion

- Severe or persistent vomiting

- High fever that is not responding to Acetaminophen (“Tylenol”) (or store brand equivalent)

- Decreased or no movement of your baby

References:

- Middlesex Health Unit – Flu (Influenza)

- CDC (updated 2017) – Pregnant and Influenza

Mumps –

What is Mumps?

Mumps is a highly contagious infection caused by a virus, spread by air, direct contact, coughing and sneezing. Although most people fully recover from mumps within 7 to 10 days, in rare cases the virus may cause complications. These include miscarriage in the first trimester, deafness, meningitis (infection of the covering of the brain and spinal cord) or infections of the breasts or ovaries.

The main symptom of mumps is painful swelling in the cheeks and neck. Symptoms can also include:

- Fever

- Headache or earache

- Tiredness

- Sore muscles

- Dry mouth

- Trouble talking, chewing or swallowing, or

- Loss of appetite

The mumps vaccine is the best way to prevent mumps as there is no specific cure. The mumps vaccine is part of the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) or measles-mumps-rubella-varicella (MMRV) immunization. It cannot be given during pregnancy. Your midwife will offer you this vaccine after your baby is born, if you test non-immune on your initial lab tests in pregnancy. You must not get pregnant for one month after the vaccination, as the MMR vaccine contains live attenuated virus, which can cause significant birth defects.

The MMR vaccine poses very minimal risks and has not been linked to Autism. You can read more about vaccine safety at the following websites:

https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/vaccines/mmr-vaccine.html

https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/concerns/autism.html

What should I do if I get mumps when I am pregnant?

Unfortunately, there is no specific treatment for mumps other than letting it run its course. We recommend staying in isolation for at least 5 days after the swelling starts. You can take Acetaminophen (“Tylenol”) for the pain and swelling and to reduce fever. Drink plenty of fluids, rest, and eat healthy foods. Avoid contact with any other household members.

If you are in early pregnancy, and experience abdominal pain or bleeding, contact your midwife for more advise.

Measles –

Measles –

What is Measles?

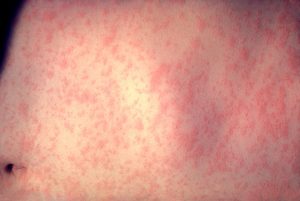

Measles known as the “Red measles” is caused by a highly contagious virus spread through direct contact, the air or objects touched by an infected person.

Symptoms begin 7 to 18 days after exposure. Initial symptoms include:

- Fever

- Cough

- Runny nose

- Sleepiness

- Irritability (feeling cranky or in a bad mood)

Small, white spots may also show up inside the mouth and throat.

After 3 to 7 days, a red blotchy rash develops on the face and spreads down the body.

Most people recover fully from measles within 2 to 3 weeks. However, measles can be especially dangerous for infants and those with weakened immune systems.

Complications can include:

- Ear infections

- Pneumonia (lung infection)

- Encephalitis (swelling of the brain), which can cause seizures, brain damage or death

The measles vaccine is the best way to prevent measles as part of the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) or measles-mumps-rubella-varicella (MMRV) immunization. It cannot be given during pregnancy and will be offered after your baby is born.

What should I do if I get measles when I am pregnant?

There is no specific treatment for measles as most people fully recover within a few weeks, however, it can be confirmed via a blood test, urine test and nasal swab that your family doctor can take. However, as measles is highly contagious, please call your doctors office first and let them know you have measles. Please do not attend any prenatal or postpartum appointments at the midwife clinic until your symptoms have fully disappeared. Your midwife will discuss the best approach to your care during the time you are most infectious. You can take Tylenol for the pain and swelling and to reduce fever. Drink plenty of fluids, rest, and eat healthy foods. You should stay at home until at least 4 days after the rash appeared.

Rubella –

What is Rubella?

Rubella is a highly contagious virus spread through direct contact, the air, coughing and sneezing. A pregnant client infected with rubella has a 90% chance of transmitting the disease to the unborn baby. It causes the most severe damage when the client is infected during the first 12 weeks of pregnancy. However, it is rare for a client who has been immunized to become infected with rubella.

Congenital Rubella Syndrome (CRS) is a condition caused by a pregnant person contracting the rubella virus and passing it onto the unborn baby. It increases the chances for miscarriage or stillbirth, and can cause significant birth defects.

Symptoms appear between 14 and 21 days after a person has been infected. The most contagious period is for the first 4 days after the rash appears. Some people who are infected with rubella will not show any symptoms. For others, symptoms usually develop 14 to 17 days after exposure. Sometimes, it takes up to 21 days for the symptoms to appear.

In children, symptoms can include:

- A rash that starts on the face and spreads to the rest of the body (lasts about 3 days)

- A low-grade fever (under 39°C)

- Nausea

- Inflammation of the lining of the eye (conjunctivitis)

In older children and adults, symptoms can also include:

- Swollen glands behind the ears and neck

- Cold-like symptoms before the rash appears

- Aching joints

The rubella vaccine is the best way to prevent rubella as part of the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) or measles-mumps-rubella-varicella (MMRV) immunization. It will be offered to you after your baby arrives if you test non-immune during pregnancy.

What should I do if I get Rubella when I’m pregnant?

You should start by seeing your family doctor or walk-in clinic to take blood tests and swabs to confirm Rubella. There is no treatment for Rubella other than rest, fluids and Tylenol. During this period, you should stay home from work or school, and we advise you cancel midwife appointments to avoid spreading the virus. Young children should not go to daycare if they are showing symptoms of rubella.

You should let your midwife know of a positive result by calling the office. If a positive result is confirmed, your midwife will refer you immediately to a specialist Obstetrician. Please note, appointments can sometimes take a few days up to a few weeks. Our office staff will let you know once we have an appointment.

References:

- Motherisk – vaccination during pregnancy

- CDC – Pregnancy and Rubella

- World Health Organization (WHO) – Safety of immunization during pregnancy; a review of the evidence.

- Government of Canada – vaccination and pregnancy

What is Zika Virus?

Zika is a virus spread to people primarily through the bite of an infected mosquito. It can also be spread through sexual intercourse. Zika infection during pregnancy can cause serious birth defects such as microcephaly and other severe brain defects.

The Government of Canada recommends that pregnant people and families planning a pregnancy should take special precautions to avoid infection with the Zika virus.

If you are pregnant, you should avoid:

- Travelling to Zika-affected country or area

- Unprotected sexual contact with anyone who has traveled to a Zika-affected country or area for the duration of your pregnancy

If you can’t avoid travel to Zika-affected countries or areas:

- Protect yourself from mosquito bites at all times by following strict mosquito bite prevention measures

- get advice from your midwife at least 6 weeks before you travel and follow-up upon your return

If your sexual partner has traveled to a Zika-affected country or area, to protect yourself and your fetus from infection, you should:

- Always use condoms correctly for the duration of your pregnancy, or

- avoid having sex for the duration of your pregnancy

For men who have traveled to a Zika-affected country or area and have a pregnant partner, you should:

- Always use condoms correctly for the duration of the pregnancy, or

- Avoid having sex for the duration of the pregnancy

There is no vaccine to prevent or medicine to treat Zika.

What should I do if I think I might have Zika?

If you think you have been exposed to or infected with the Zika virus, contact your family doctor or attend a walk-in clinic as soon as possible. They will be able to arrange testing for Zika for you.

Midwives of Ontario unfortunately cannot request Zika testing, but please inform us of any positive results immediately so that we can refer you to one of our specialist Obstetricians. Please note: Referrals can take a few days sometimes up to a few weeks. Your midwife will discuss your referral with you and our staff will contact you when she has an appointment with the obstetrician.

References:

- CDC (2018) – Zika and pregnancy

What is Pertussis (whooping cough)?

Pertussis, also known as whooping cough, is a contagious infection of the lungs and airways. It is caused by bacteria called bordetella pertussis that can be spread in the air by coughing or sneezing by an infected person. Pertussis is a disease that happens year-round everywhere in the world.

Each year in Canada between 1,000 and 3,000 people fall ill from pertussis. Worldwide, there are about 20 to 40 million cases of and 400,000 deaths from pertussis each year.

Between the years 2012 and 2015 numerous outbreaks in Canada occurred. 70% of these admissions were babies under the age of 4 months old, and 14 out of 15 babies died from pertussis under 2 months old, before the infants received their first vaccinations.

What are the symptoms of Pertussis?

The first symptoms of pertussis may show up 7 to 10 days after being infected but could appear up to 28 days after infection. Symptoms include a mild fever, runny nose, red watery eyes and a cough. It leads to serious coughing fits that can last for two to 8 weeks. The coughing fits may cause difficulty breathing, choking and vomiting. The coughing can be so intense it causes a “whooping” sound.

Without treatment, pertussis can last for weeks or months, and can cause brain damage or even death. It is most dangerous for children under 1 year old, especially if they are unvaccinated or under-vaccinated. It is important that you and your children receive all vaccinations for protection of yourself and others.

How can I protect myself during pregnancy and my family?

The Canadian National Advisory Committee (NACI) and The Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecologist of Canada (SOGC) recommends vaccination with the Tdap vaccine (Tetanus Toxoid, Reduced Diphtheria Toxoid, and Reduced Acellular Pertussis) in every pregnancy ideally between 21 weeks and 32 weeks of pregnancy. You should see your family doctor to receive this vaccination during your pregnancy, as our office currently does not have a medical fridge to correctly store this vaccine.

Evidence supports having Tdap vaccination as early as 13 weeks of pregnancy until birth. However, having the vaccine after 32 weeks may mean the antibody levels may not be sufficient to protect your baby as it takes at least four weeks after vaccination to reach peak anti-pertussis antibody levels.

The pertussis vaccine is given by needle and is very safe for you and your baby. It can also be administered to clients who are breastfeeding. Side effects of a pertussis vaccine are very mild and usually go away within a few days. Studies have shown that 9 out of 10 babies under 3 months of age are protected following client vaccination against pertussis during pregnancy.

A child under 6 years old needs five doses of the pertussis vaccine known as DTaP, starting at 2 months of age. Protection from the vaccine fades over time, so it’s important to get a booster dose known as Tdap.

What should I do if I get whooping cough and have never been vaccinated?

We recommend you see your family doctor or attend a walk-in clinic as soon as possible. Whooping cough can be diagnosed using laboratory testing and physical examination. You will be given antibiotics to treat Pertussis. You can also receive an immunization even with suspected or confirmed pertussis, as you still may not produce sufficient antibody levels to protect your baby after a natural infection.

If you are not sure that you have pertussis or you have been diagnosed with pertussis, stay away from young children and infants, and see your family doctor for an immunization. Stay isolated for three weeks after your cough started, or until your cough ends, whichever comes first. Make sure the people you are in contact with are fully immunized against pertussis. If they are not immunized, they should see their health care provider for an immunization. Be mindful that not everyone may have received all their recommended vaccines, especially young babies.

References:

- SOGC – vaccination against Pertussis (whooping cough) during pregnancy in Canada.

- CDC Government of Canada – Pertussis (whooping cough)

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a common virus that is usually harmless. Sometimes it causes problems in babies if you get it during pregnancy (congenital CMV).

What is cytomegalovirus?

CMV is related to the herpes virus that causes cold sores and chickenpox. Once you have the virus, it stays in your body for the rest of your life. Your immune system usually controls the virus and most people do not realise they have it. But CMV can cause serious health problems in some babies who get the virus before birth, and in people who have a weakened immune system.

Congenital CMV infection is acquired in utero via the placenta and and is present at birth. It is estimated to affect 1 of every 180 to 240 babies born in Canada. Although most infants with cCMV are healthy at birth, approximately 15% to 20% have permanent neurologic sequelae, most commonly hearing loss; other sequelae include intellectual disability, cerebral palsy, visual impairment, and seizures.

What are the symptoms of CMV?

CMV does not usually cause symptoms. Some people get flu-like symptoms the first time they get CMV, including:

- fever

- aching muscles

- tiredness

- skin rash

- nausea

- sore throat

- swollen glands

If you do have symptoms, they usually get better without treatment within about 3 weeks. You should notify your midwife of possible infection so that a blood test can be arranged during your pregnancy to confirm infection and follow up as required. After birth, babies sometimes require anti viral medication to treat the infection. There is currently no treatment during pregnancy, but in most cases the virus does not cause problems for your baby.

How is CMV spread?

CMV is mainly spread through close contact with someone who already has CMV. It can be passed on through sexual contact and contact with other body fluids including saliva, blood, breast milk, tears, urine and faeces.

CMV can only be passed on when it’s “active”. The virus is active when:

- you get CMV for the first time – young children often get CMV for the first time at daycare or school

- the virus has “re-activated” – because you have a weakened immune system

- you’ve been re-infected – with a different type (strain) of CMV

Pregnant clients can pass an “active” CMV infection on to their unborn baby. This is known as congenital CMV.

How can I reduce the chance of getting CMV during pregnancy?

The best way to reduce the chance of getting CMV during pregnancy is to:

- wash your hands using soap and water – especially after changing diapers, feeding young children or wiping their nose

- regularly wash toys or other items that may have young children’s saliva or urine on them

- avoid sharing food, cutlery and drinking glasses or putting a child’s pacifier in your mouth

- avoid kissing young children on their mouth

There’s currently no vaccine for CMV.

References: